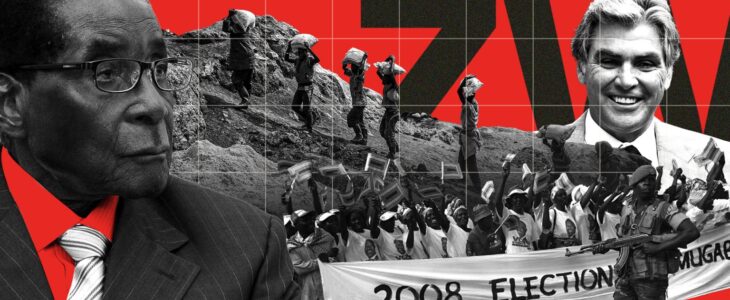

In 2008, Zimbabwe was at a turning point. President Robert Mugabe faced electoral defeat by pro-democracy challengers for the first time in two decades. Suddenly, his cash-starved regime received a surprise $100 million, which it allegedly funneled into a violent campaign that enforced the status quo, and kept Zimbabwe on the road to an economic disaster from which it is yet to recover.

Now, leaked data from Swiss banking giant Credit Suisse has shed new light on the role the bank played in the deal that saved Mugabe from potential defeat, and blocked an opportunity for political and economic reform.

The $100 million came from the sale of platinum mining rights that Mr Mugabe’s government had quickly appropriated, then given to a company owned by Muller Conrad “Billy” Rautenbach, a longtime friend of the regime. Mr Mugabe’s regime used the proceeds of the deal to pay for the president’s campaign of violence, according to multiple reports.

Mr Rautenbach and Credit Suisse knew each other well. They both owned a large share of the same company: Central African Mining and Exploration Company (CAMEC). By mid-2007 the bank owned six percent of CAMEC through its London-based investment subsidiary, Credit Suisse Securities Ltd.

Credit Suisse touted Rautenbach as a key asset in the region. Its mining analysts promoted CAMEC in the press and in briefing notes, telling investors the company was a “new major in the making,” and a possible rival to mining behemoth Xstrata.

Credit Suisse also gave CAMEC, which was listed on London’s Alternative Investment Market index, a $60 million line of credit, which the company fully used.

On March 4, 2008, a chain of events began that would quickly get the Mugabe administration the money it needed for its re-election campaign while also earning Rautenbach a sizable profit. It started when Rautenbach opened two accounts with Credit Suisse, according to leaked bank records that are part of the Suisse Secrets investigation, coordinated by OCCRP and based on a huge trove of banking data leaked to Süddeutsche Zeitung.

The Suisse Secrets Investigationⓘ

Suisse Secrets is a collaborative journalism project based on leaked bank account data from Swiss banking giant Credit Suisse.

The data was provided by an anonymous source to the German newspaper Süddeutsche Zeitung, which shared it with OCCRP and 46 other media partners around the world. Reporters on five continents combed through thousands of bank records, interviewed insiders, regulators, and criminal prosecutors, and dug into court records and financial disclosures to corroborate their findings. The data covers over 18,000 accounts that were open from the 1940s until well into the last decade. Together, they held funds worth more than $100 billion.

“I believe that Swiss banking secrecy laws are immoral,” the source of the data said in a statement. “The pretext of protecting financial privacy is merely a fig leaf covering the shameful role of Swiss banks as collaborators of tax evaders. This situation enables corruption and starves developing countries of much-needed tax revenue.”

Because the Credit Suisse data obtained by journalists is incomplete, there are a number of important caveats to be kept in mind when interpreting it. Read more about the project, where the data came from, and what it means.

Then, two weeks later, the Zimbabwean government strong armed mining company Anglo American into handing over a tranche of land that included the rights for mining platinum there. The government immediately transferred those rights to Rautenbach’s offshore company and a state mining company.

CAMEC announced a few days later, on March 28, that it would issue 200 million shares of its stock worth about 100 million British pounds ($1.99 million). One of the buyers that helped finance the controversial deal was reportedly Credit Suisse, which bought an unknown number of shares. The majority of shares was bought by Och-Ziff Capital Management Group, a U.S.-based hedge fund (now called Sculptor Capital Management).

Two weeks later, on April 11, 2008, CAMEC bought out Rautenbach’s company for $5 million and 215 million CAMEC shares. CAMEC provided its new company with $100 million to enable it “to comply with its contractual obligations” to Mugabe’s government, according to CAMEC’s stock market filings. But the money does not appear to have been used for meeting any obligation, or doing any mining. Instead, the company was widely reported to have transferred the funds to Mugabe’s ZANU-PF political party.

With a flurry of activity, the entire process was completed in less than three weeks. CAMEC had its mining rights, the Mugabe regime had $100 million, and Rautenbach had pocketed a substantial sum.ⓘ

A former executive at the mining company that had to give up the platinum rights, speaking anonymously due to the risks posed by commenting, said it was obvious they had to comply.

“There was no doubt our presence [in Zimbabwe] was under threat had we not agreed to the surrender of land,” he said, adding that Rautenbach and CAMEC “relied solely on…political connections.”

Documents from a U.K. government corruption investigation looking at mining deals in central Africa, obtained by OCCRP, showed CAMEC may have acquired “tainted assets from those who engage in corruption.”

The $100 million arrived within weeks of Mr Mugabe losing the first round of elections to opposition leader Morgan Tsvangirai. With a run-off vote looming, and money in the bank to pay thugs and supporters, the C set to work delivering on a threat to punish anyone who betrayed them at the ballot box.

Within days of the money arriving, a three-month campaign of terror had started.

![President Robert Mugabe in 2015. [Credit: Press Service of the President of Russia]](https://i1.wp.com/media.premiumtimesng.com/wp-content/files/2022/02/President-Robert-Mugabe.jpg?resize=1200%2C740&ssl=1)

Soldiers and armed gangs unleashed Operation Makavhoterapapi? (‘Where did you put your vote?’), in which more than 100 people were killed and over 1,000 attacked. Opposition leader Tsvangirai was forced to flee the country only four days after the $100 million arrived with the regime. With the opposition decimated by violence, Mugabe went uncontested into the next round.Advertisements

“That money totally brought about all the heartache, pain, gerrymandering, violence, intimidation, repression that took place at the 2008 election,” said Roy Bennett, a former anti-Mugabe politician, on a Zimbabwean radio show in 2012. “[The election violence] is directly linked to that $100 million.”

Three days after the platinum deal closed, and as Zimbabwe descended into violence, a Credit Suisse research paperlauded CAMEC as one of its “African 20” stock picks.

There is no evidence that Credit Suisse knew about the planned corruption but it should have seen that the deal was suspicious. A classifiedU.S. State Department cable, sent May 23, 2008, and later released by Wikileaks, described the sale as a “swiftly concluded and murky deal.”

Mining Controversy

Rautenbach was already a controversial figure when Credit Suisse opened his accounts in early March 2008, having fled fraud charges in South Africa and been deported from the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) for mining-related corruption. A 2006 U.N. reportquestioned Mr Rautenbach’s integrity and criticized inadequate due diligence on his DRC mining deals.

Mr Rautenbach’s accounts at Credit Suisse were open for several months after both the U.S. and EU sanctioned him for his role in subverting Zimbabwe’s democracy. It’s not clear if Rautenbach closed them or if the bank acted.