— Alison MaduekeIn July 1966, Admiral Alison Madueke was due to begin a training programme at the Britannia Royal Naval College, Dartmouth, UK, when the Ironsi regime was overthrown. In the following excerpt, he recounts his narrow escape from the massacres that occurred during the 1966 counter-coup:

I“After breakfast, Midshipmen Obianwu, Mohammed and I were taken in two Nigerian Navy staff cars to the Ikeja Airport, to catch our flight for London after obtaining the clearance of the Captain. Out of the Naval Base, we noticed a very scanty Lagos traffic for that time of the morning. As soon as we got to the airport, the atmosphere got more eerie. I was assailed by some uneasiness and suspicion, so I went up to the desk and asked about our flight to London, receiving confirmation that it would operate. I then wanted to confirm that my name was on the list.”

II“On going through the manifest which was at the check-in-counter, I noticed that my name, that of George Obianwu and a certain Mrs. Ike were asterisked. I made a mental calculation and decided there was something fishy. The asterisked names were those of Ndigbo, so what was the matter? As I was still trying to make sense of this development, I noticed a policeman standing near the check-in counter. I called him and asked him: ‘What is going on here?’ ‘Ah, Oga, soldiers are in control here o’, he replied. ‘I hear they are killing Igbo Officers o! . . .”

III“[After boarding the flight] the aircraft started taxiing in readiness for takeoff. But midway, as it gathered speed, the attempt was aborted. The aircraft came to stand still for sometime before returning to where we had embarked. The pilot’s voice came through the intercom. ’This is the Captain speaking. Will the three Naval officers flying to London please alight. They are wanted by the military authorities.’ I felt a knot in the pit of my stomach, I felt like someone in a daze. The message was repeated. At that point, of course, I thought the game was up.”

IV“We got down from the aircraft. Ibrahim Mohammed was first on the gangway: I was following him and lo and behold, two armored vehicles and over 20 soldiers in full Battle Order were afoot awaiting us. Ibrahim was the first to alight, he pulled out his passport and asked the soldiers, “Me, too?” Passports in those days usually had the owner’s name boldly displayed on the cover.”

V“The soldier replied, “No, you go back.” He did as he was ordered. When I came down, the soldier ordered I should enter a jeep parked nearby. Obianwu came down and was handed the same order. So I asked the soldier that gave the instruction, “What of my luggage?” For an answer, I got hit on my shoulder with the butt of his gun. “You still de think of your luggage,” he sneered as he struck me again. “Enter jeep!” he yelled at me. It was now obvious that we were in deep trouble. We climbed into the open Land Rover and four soldiers armed with machine guns sat on either side of George and I. The soldiers drove us to a building at the fringe of the airport, the command post and coordination centre for all their operations.”

VI“Inside the office sat a white man behind an executive office desk, a man who I was later told was a lecturer at the Ahmadu Bello University, Zaria, a Mr. Boyd. We were herded to his table for an instant interview. Meanwhile, armed soldiers milled around the whole place, a lot of them drunk and looking fierce with their bloodshot eyes. When I faced our interrogator, he started asking questions that were rather obvious in their implications. ‘Where were two of you on the 15 of January this year?’ That was the day of the first Military coup, a coup that was now lagged an Igbo coup which left casualties of mostly Northern origin. ‘We were in Kaduna.’ I responded.”

VII“Once I said that, [Mr Boyd] turned round to the officers and men surrounding him and emphasized, ‘You see?’ Turning back to me he continued. ‘How many of you Cadets joined the Navy?’

‘Five’.

‘How many are from the North?’

‘One.’

He turned round again to the soldiers.

‘You see?’

Facing me again he ordered that we should walk out and into the courtyard. That meant ‘Go out and be shot’. I thought the man was too presumptuous.

‘No. Not on your life’, I retorted. ‘I am not going out there. Why do you think I should go out there?’

‘Because I said you should go out there’, he said with a note of finality.”

VIII“I had now become very angry and ready to damn any consequences, knowing what going out there portended.

‘By the way who are you?’ I asked. ‘What right have you got to question me in my country? Are you a Nigerian? You cannot order me around my friend. I am a commissioned officer of this country and I am staying here, yes here will I stay!’

It was [Mr Boyd’s] turn to get angry. He asked the soldiers to push us out. Immediately, as they made for us, I called out to Dickson who was at the other end of the room but within earshot of the exchanges. ‘Major Dickson, you are here and this kind of thing is happening.’ Dickson was taken aback. He didn’t know who I was.”

IX“He turned to me.

‘Yes, who are you?’ he asked.

‘I am Alison Madueke.’

‘Which Madueke?’

‘The Madueke in Otukpo. My elder sister, Cordelia, was your classmate at Methodist Central School.’ For some moments Dickson stood transfixed, his armed men waiting for direction on what next to do.

‘Do you know Mr. Oniya?’ asked Dickson.

‘Yes, Mr. Oniya is the owner of Niger Hotel, Otukpo. He lives right opposite your house.’

‘Apo Idoma?’, he asked in his native Idoma language, meaning, ‘Do you speak Idoma?’

‘Mpo ligi.’ ‘Yes, a little.’

And that did it.

I remembered vaguely too that there was a time my father’s and his uncle’s vehicles had some problems. They had torn the tarpaulin of my father’s vehicle and when the matter was brought to my father’s notice, he ordered the driver to forget the damage. That was an event I remembered and quickly mentioned to identify my family. Dickson remembered.”

X“Meanwhile George Obianwu had become very jittery and frightened by our plight and started to cry. I told him in lgbo language to cut the tears because it was not a crying matter but a matter of our living or getting killed. Dickson thought for a while, turned to his men and asked them to let us stay for the time being. We were asked to resume our seats and later re-seated in an adjoining section of the hall. We did so as the white man [Mr Boyd] watched us, fuming like a cat whose prey had been snatched.”

XI“After a while, Dickson left the room to confer with his troops because, frankly, the way they were eyeing us suggested that they could start firing at us through the window if not assuaged one way or another. What Dickson told his men was that we were not Nigerians, that we were Ghanaian students; there had been a terrible mistake. Thank God they were not privy to the exchanges in the room.”

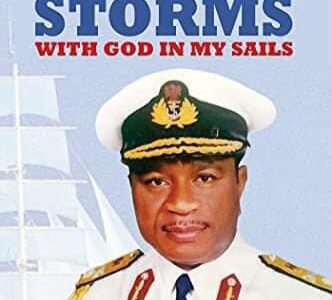

•Credit: Alison Madueke, RIDING THE STORMS WITH GOD IN MY SAILS (Ekpen Media, 2019)