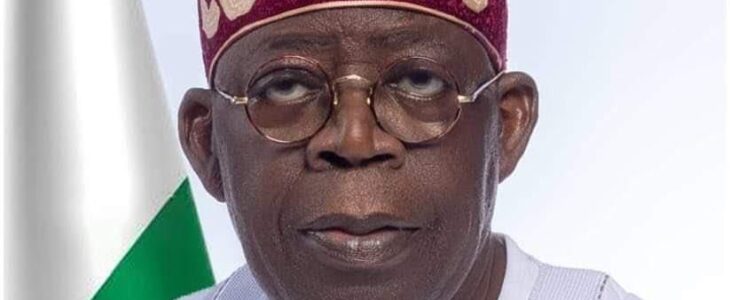

By now, discerning citizens should have got accustomed to President Bola Ahmed Tinubu’s style of administration. Rightly or wrongly, his leadership approach has been likened to that of Lee Kuan Yew, the former Prime Minister of Singapore, regarding vision and the willingness to make tough decisions. It can not be safely argued, though, that he has the passion to fight corruption as Yew had. While his style has garnered tremendous praise, it has also faced equally matched criticism for being overly focused on consolidating power with a sinister intent.

But every student of power knows power is a double-edged sword.

Its positive connotation suggests that great power must also come with great responsibility. Looking at power from another perspective, it is argued that the greater the power, the more dangerous the abuse.

Interestingly, both have their places in history.

Since we know him as President,

successfully implemented multiple police forces. These nations have recognised the value of decentralised policing in addressing unique security challenges and promoting effective law enforcement.

For instance, the US Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) works in tandem with state-level police departments to tackle crimes that transcend state borders. Similarly, Germany’s state police forces (Landespolizei) collaborate with federal agencies to maintain law and order.

State police forces would be better equipped to respond to local security threats, build trust with communities, and provide critical support to national security efforts. Today, there are 17,985 police agencies in the United States, 48police forces in the United Kingdom, which is a unitary state. India, as fragmented and diverse as Nigeria, offers an incredible lesson in effective policing. The Indian Constitution establishes a legislative and executive division between the centre and the states.

First, the police are a subject under the state government, according to the 7th schedule of the Constitution. As a result, each of India’s 28 states has established its police force. Second, police forces in states are primarily responsible for local issues such as crime prevention and investigation and maintaining law and order. Strikingly, they also provide the first response in more severe internal security challenges, such as terrorist incidents or insurgency-related violence.

Third, the central government’s seven police forces and several other police organisations are to assist states in maintaining law and order, especially in specialised tasks such as intelligence gathering, investigation, research, record-keeping, and training. There are enough templates to learn from.

No doubt, several challenges must be addressed. Nigeria’s constitution would need to be reviewed and amended to accommodate state police forces. The tendency of its abuse by state governors can be clinically considered in the Constitution. Additionally, state police forces would require significant funding and resources, potentially straining state budgets. This will also require a revenue allocation formula review. In all, the fears and reservations of the doubting Thomases appear negligible in the face of horrendous crimes that assail our sensibility daily.

By embracing decentralised policing, Nigeria can promote a culture of transparency, build trust with communities, and enhance its response to security challenges. As the nation continues to grapple with the complexities of modern security, it is clear that a new approach is needed – one that prioritises local solutions, community engagement, and effective collaboration between state and federal agencies.

President Tinubu can pull it through as the opposition to the creation of state police has significantly reduced, especially in the North. It would mark a significant shift towards more effective and accountable security governance, a robust economic revival and a productive federal system. This is one public policy where the President can use great power with great responsibility. And history will be kind to him.

Credit: Leadership