The U.S. is cranking up the pressure on Russian President Vladimir Putin to stay out of Ukraine by threatening to block the opening of a Russian-owned natural gas pipeline.

The State Department put Putin on notice Thursday that the Nord Stream 2 pipeline would not be allowed to operate if Russia invades Ukraine.

“If Russia invades Ukraine, one way or another, Nord Stream 2 will not move forward,” Victoria Nuland, undersecretary of state for political affairs, told reporters in Washington.

Nuland offered no details of how the U.S. would keep the Russia-to-Germany pipeline from opening but said the U.S. would work with Germany to make sure it does not become operational.

The pipeline “is currently a hunk of metal on the bottom of the ocean,” she said. “It needs to be certified. It needs to have regulatory approval. And no gas will flow through it” until those steps are completed.

Here’s a look at how Nord Stream 2 became a bargaining chip in the crisis between Russia and Ukraine:

What is Nord Stream 2?

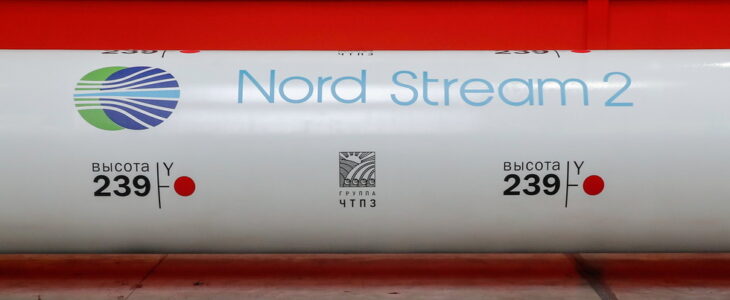

Nord Stream 2 is a controversial $11 billion, Russian-owned natural gas pipeline that snakes westward from Russia to northeastern Germany for more than 700 miles under the Baltic Sea. The pipeline was launched in 2015 and follows a similar route to another pipeline, Nord Stream 1, which was completed in 2011.

Owned by Gazprom, a Russian state-controlled company, Nord Stream 2 was completed last year and has the capacity to handle 55 billion cubic meters of gas per year once it becomes operational.

Why is the pipeline important?

Russia has the largest gas reserves in the world, and Nord Stream 2 would make it easier for Moscow to keep natural gas flowing into Europe.

But skeptics fear that Putin has a more sinister motive: By controlling the flow of gas into Europe, Putin also has the ability to exert political influence over European countries. Put simply: To get what he wants, he could simply threaten to turn off the spigot.

That could put countries like Germany, which imports most of its gas, in an untenable position: Cede to Putin’s geopolitical demands or risk leaving much of your country in the cold.

UKRAINE TENSIONS: Biden, Democrats call for sanctions on Putin, other top Russian officials if Kremlin invades Ukraine

BETTER TRAINED, BETTER EQUIPPED:What you should know about Russia and Ukraine’s militaries

What does this have to do with Ukraine?

Right now, Russia transports gas to its customers in central and eastern Europe over land routes that run through the Baltic states and Ukraine. Russia pays Ukraine around $2 billion a year in transit fees.

Nord Stream 2 would allow Russia to bypass Ukraine when pumping gas to Europe, which means it could eventually avoid paying the transit fees. An agreement negotiated between the countries in 2019 would require Russia to pay a minimum transit fee even if it doesn’t pump a certain volume of gas through Ukraine. But that agreement is set to expire after five years.

The transit fees make up about 5% of Ukraine’s budget, so the loss of that money would deal a significant blow to the country’s finances. Ukraine is one of the poorest countries in Europe.

Where does Europe stand?

The governments of Germany and Austria support Nord Stream 2, but other countries, including Ukraine, the Czech Republic, Poland, Romania, Estonia and Croatia, have all spoken out against the pipeline, arguing that it poses major energy security risks for central and Eastern Europe.

Germany’s energy regulator announced in November that it had suspended the approval process for Nord Stream 2 because the Swiss-based company that will operate pipeline needed to set up a German subsidiary before it could get an operating license.

“My sense is that (approval) is not going to happen until midway through next year, and a lot of this is going to depend on what the German government does,” said Daniel Kochis, senior policy analyst in European affairs for the Heritage Foundation, a conservative think tank based in Washington.

Where does the U.S. stand?

Nord Stream 2 has faced widespread opposition in Washington among Republicans and Democrats, who argue it would increase Russia’s economic and political leverage over Europe.

Then-President Donald Trump tried to sink the pipeline by claiming it would make Germany “captive to Russia.”

President Joe Biden also opposes the pipeline, yet in May his administration waived sanctions on the pipeline’s operator as the U.S. tried to rebuild ties with Germany, which had seriously frayed under Trump.

Earlier this month, Senate Democrats blocked a bill by Sen. Ted Cruz, R-Texas, that would have required the president to impose sanctions on entities overseeing Nord Stream 2 regardless of whether Russia attacks Ukraine.

Democrats countered with their own legislation that would personally sanction Putin and members of his inner circle if the Kremlin invades Ukraine. Lawmakers have not voted on that legislation.

Meanwhile, Biden and European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen issued a joint statement Friday vowing to work together to shore up Europe’s energy security and “to avoid supply shocks, including those that could result from a further Russian invasion of Ukraine.”

They said the U.S. and EU were collaborating with other countries and suppliers to identify “additional volumes of natural gas to Europe from diverse sources across the globe.”

What’s next?

Germany’s new chancellor, Olaf Scholz, will meet with Biden at the White House on Feb. 7 to discuss Russian aggression toward Ukraine and other issues. Nord Stream 2 also is expected to be on the agenda.

Echoing the State Department’s warning that Nord Stream 2 would not be allowed to open if Russia invades Ukraine, German Foreign Minister Annalena Baerbock also promised consequences against Russia if it attacks.

Germany is working on “a strong package of sanctions” that would cover several areas, including Nord Stream 2, Baerbock told parliament on Thursday.

In dropping its sanctions and allowing Nord Stream 2 to be completed, the U.S. said it received assurances from Germany that the pipeline would not be allowed to operate if Russia invades Ukraine. But what exactly that might involve – and how they are defining invasion – remains unclear.

Scholz “has been much more circumspect about it,” Kochis said. “He has basically taken the same position as the previous (German) government that this is an economic project, that it should be separate from politics. And he hasn’t been willing to say publicly at least that he would shut down this pipeline.”

Though the U.S. insists the pipeline won’t go forward if Russia invades Ukraine, “there is not really a lot of leverage that the U.S. has unless the Germans agree to stop the regulatory approval,” said Margarita Balmaceda, a professor of diplomacy and international relations at Seton Hall University and the author of Russian Energy Chains: The Remaking of Technopolitics from Siberia to Ukraine to the European Union.

Government officials and analysts will be watching Scholz’s meeting with Biden to see if he signals his next step.

Credit: Yahoo.com