Anew dimension has been added to the search for a lasting solution to Nigeria’s festering security challenge: a proposal by some stakeholders urging the government to set up a special Commission of Inquiry to investigate the role of present and past public office holders in the escalating trend of terrorism, kidnapping, and banditry.

The aim, according to the proponents, is to identify the root cause of the problem and offer a solution for enduring peace and stability in the country. This is a significant suggestion that touches on the fundamental causes and political dimensions of Nigeria’s complex security challenges.

Yet, opinion is divided on the composition, the scope and modalities for the implementation of the proposal. For instance, the pioneer chairman of the defunct Alliance for Democracy (AD), Abdulkarim Daiyabu, wants the scope to cover the period between 1985 and 2025, as well as prosecution of all those who have a hand in the promotion or sponsoring of criminality.

“It is high time we, the people of this country, who are recipients of these crimes insisted on constituting a judicial commission of enquiry to investigate everyone who have been part of the government from 1985 to 2025 so that whosoever is found guilty of any crime can be tried and prosecuted. If need be, all their property either at home or abroad should be confiscated. Those who are directly found culpable should be sentenced to death either by shooting or hanging,” he said in his proposition.

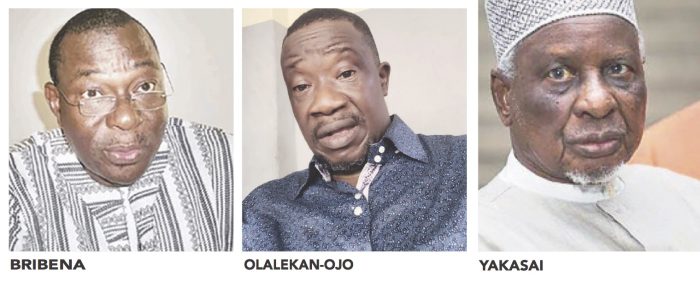

In contrast, Jackson Olalekan-Ojo, a prominent security analyst, proposes what he called a discreet security summit that will involve retired military and paramilitary personnel, serving military and paramilitary members, renowned scholars, university dons, first class traditional rulers, youth leaders, political gladiators, and security experts — without anyone knowing about their invitation. Their activities, he said, won’t be public. The purpose of the summit, he explains, “isn’t to punish past offenders but to offer solutions and destabilise those promoting or sponsoring criminality.”

He said: “People like us have been calling for a discreet security summit — a summit known only to those invited — to investigate the past, assess the present, and offer solutions to the country’s security situation. But the government isn’t yielding.

“Now, there’s a suggestion to investigate past and present leaders or office holders to determine their role in the current security challenge. Things like this can never see the light of day because most people in the present government have been governors of their respective states for the past eight years.

“For example, the current SGF was a governor and a minister before his present appointment. How can someone like him be in government and you want to investigate his past? Some ministers were also governors for eight years — how can you now investigate their past? This is a suggestion that won’t see the light of day.

“At the end of the day, it’ll turn into a political jamboree where the principle of cover me, I cover you will reign. In the end, it’ll be a waste of taxpayers’ money.

For the states, Section 5(1)(b) and relevant state laws like the Commission of Inquiry Law of a state give governors similar powers to establish commissions of inquiry for their states. These provisions allow the executive to investigate matters of public importance, including security challenges, and make recommendations for action.

Such a commission may be tasked with investigating the conduct of officials, seeking assistance from government departments, summoning witnesses, and producing a detailed report with opinions and recommendations.

This contrasts slightly with a Judicial Commission which often implies that it would be headed by a serving or retired judge, lending it significant legal authority and public credibility.

A judicial commission could officially identify specific past and present functionaries whose actions or inactions contributed to the festering insecurity. It could also provide a detailed public record of the institutional and governance failings that have prolonged the crisis and offer recommendations for legislative, policy, and security sector reforms based on its findings.

Both ways, the commission’s findings would be recommendations, not judicial verdicts. According to legal experts, prosecution would still require the Attorney-General’s office and the regular court system.

Many past commissions of inquiry in Nigeria have had their reports shelved or watered down by government, leading to little tangible action or prosecution.

In the present circumstance, the suggestion to set up such a judicial commission reflects the deep-seated mistrust in the government’s responses to insecurity and the public demand for a high degree of transparency and accountability in dealing with the issue.

Political expediency

Either case, the proposal for a special commission stems from a widely held belief that insecurity in Nigeria is exacerbated, if not directly caused, by governance deficits: a failure to address the socio-economic root causes of insecurity, such as poverty, high youth unemployment, and lack of social justice.

Secondly, there is a widespread allegation that funds meant for security or development are misappropriated, weakening the capacity of security agencies. This speaks to corruption allegedly institutionalized by political leadership contributing to the crisis.

Many analysts are often quick to blame the failure of security forces to effectively contain insurgency, banditry and kidnapping on poor equipment, training, and sometimes, the poor attitude of personnel.

Additionally, there is an insinuation linking insecurity with political exclusion, especially where such grievance is not adequately addressed, leading to violence.

Previous experience

Nigeria has a long tradition of setting up Commissions of Inquiry, especially in response to major crises, unrest, or allegations of corruption. However, such initiative often ends up as a talk show. Former President Olusegun Obasanjo, upon assumption of office in 1999, set up the Human Rights Violations Investigation Commission otherwise known as Oputa Panel to investigate gross human rights violations committed from January 15, 1966, to May 29, 1999, covering the military era. It was essentially a truth and reconciliation commission, often referred to as the Nigerian Truth Commission. It extensively documented state-sanctioned violence, abuses by military personnel, extrajudicial killings, and political assassinations like Dele Giwa’s murder, directly investigating the conduct of past heads of state and their security operatives.

The panel submitted a detailed report in 2002. However, former military leaders who were invited challenged the panel’s authority in court, preventing their mandatory appearance. The Federal Government, after receiving the report, issued a White Paper that effectively shelved and suppressed many of its findings and key recommendations, preventing legal accountability for senior figures.

Across Nigeria, especially in states like Plateau, Kaduna, and Rivers, numerous judicial or administrative panels have been established to investigate episodes of communal violence, often with underlying security and political issues.

For example, Jos Crisis Commissions set up to investigate the underlying causes of recurring ethno-religious violence-2008, 2010 crises in Plateau State ended up with little or no significant results. The panel identified structural issues like exclusionary politics, the indigene/settler dichotomy, and the complicity/inefficiency of security agencies. While the reports documented the causes and recommended prosecution of perpetrators, including politicians and security officials, they were generally viewed as ineffective, with recommendations rarely implemented to secure prosecution or prevent future violence.

The same scenario played out in the Zaria Massacre Inquiry, Kaduna State, in 2015. The setting up of the commission followed the clash between the Nigerian Army and the Islamic Movement in Nigeria (IMN). In its submission, the Judicial Commission blamed the use of excessive force by the Nigerian Army and recommended the prosecution of the soldiers involved. But critics argued that the panel was biased and that the victims’ perspective was suppressed. Up till date, the overall effectiveness in securing justice for all victims remains highly contested. Similarly, the Rivers State Commission set up to investigate the killings and violence surrounding the 2015 elections documented numerous violations and found evidence of security agencies being unwilling or unable to attend to incidents of political violence. The report highlighted issues of political interference in security matters, but subsequent action against high-profile political actors showed a lack of political will.

Public scepticism

Based on the past experiences, there’s general scepticism about the desirability or otherwise of setting up of a commission of inquiry to investigate the current insecurity. Prominent leaders of thought who spoke with Sunday Sun, argue that its success depends entirely on the political will of the government to implement its potentially damning recommendations.

The Secretary General of the Ijaw Elders Forum (IEF), Mr Efiye Bribena, in a telephone chat, dismissed the call as unnecessary, adding that information about individuals allegedly involved in terrorism financing was already in the public domain. His words: “I won’t align with that solution. The reason is there are many reports in the public space about involvement of people in the present and past government in terrorism financing, kidnapping, and banditry. “The question is: Do we need a public enquiry to put those facts together? Most times, setting up a commission of enquiry is just a way of burying information. I’m sure the DSS and other security agencies have a lot more information than we have in the public domain.

“So why can’t the government act on the available information instead of setting up another commission of inquiry? In most cases, the reports don’t see the light of day. Organising a Security Summit will also be another talk show.

“The point I’m trying to make is the facts are already there. As far as I’m concerned, what we need is government action, not another talk show. Why do we need a summit to address a problem we refuse to accept?

“Obviously, if nothing is done drastically, we may be heading toward a state of anarchy. It’s a challenge the government needs to summon the will to deal with. I believe if they have the will, they can manage it. But they have to look themselves in the mirror and tell themselves the truth.

Public scepticism

Based on the past experiences, there’s general scepticism about the desirability or otherwise of setting up of a commission of inquiry to investigate the current insecurity. Prominent leaders of thought who spoke with Sunday Sun, argue that its success depends entirely on the political will of the government to implement its potentially damning recommendations.

The Secretary General of the Ijaw Elders Forum (IEF), Mr Efiye Bribena, in a telephone chat, dismissed the call as unnecessary, adding that information about individuals allegedly involved in terrorism financing was already in the public domain. His words: “I won’t align with that solution. The reason is there are many reports in the public space about involvement of people in the present and past government in terrorism financing, kidnapping, and banditry. “The question is: Do we need a public enquiry to put those facts together? Most times, setting up a commission of enquiry is just a way of burying information. I’m sure the DSS and other security agencies have a lot more information than we have in the public domain.

“So why can’t the government act on the available information instead of setting up another commission of inquiry? In most cases, the reports don’t see the light of day. Organising a Security Summit will also be another talk show.

“The point I’m trying to make is the facts are already there. As far as I’m concerned, what we need is government action, not another talk show. Why do we need a summit to address a problem we refuse to accept?

“Obviously, if nothing is done drastically, we may be heading toward a state of anarchy. It’s a challenge the government needs to summon the will to deal with. I believe if they have the will, they can manage it. But they have to look themselves in the mirror and tell themselves the truth.

Credit: The Sun