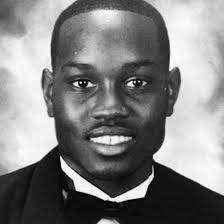

From the beginning, William Bryan has portrayed himself as a concerned citizen, one drawn by commotion when he pulled out his phone and filmed the fatal encounter between two of his white neighbors and Ahmaud Arbery, a 25-year-old black man who was running in their neighborhood.

On Friday, the authorities said Bryan, who also is white, had been more than a bystander, and had done more than record the final 30 seconds of Arbery’s life.

In charging him with murder, officials said that Bryan, who had joined the pursuit of Arbery and filmed the confrontation in late February from a short distance, had contributed to his death by attempting to “confine and detain” Arbery with his vehicle. Bryan, 50, was also charged with criminal attempt to commit false imprisonment.

“If we believed he was a witness, we wouldn’t have arrested him,” Vic Reynolds, the director of the Georgia Bureau of Investigation, told reporters at a news conference on Friday.

When the chilling video was posted online more than two months after Arbery was killed on Feb. 23, it provoked widespread outrage. Until that point, local activists had struggled to draw broader national attention to the case under the shadow of the coronavirus pandemic.

The video’s release also instigated sweeping investigations into the killing, the Glynn County Police Department’s handling of the case and eventually murder charges against three men, including Bryan, who was arrested on Thursday evening.

Kevin Gough, Bryan’s lawyer, said in a statement on Friday that Bryan had cooperated with law enforcement since the day of the shooting. “It feels like the only thing that has changed” regarding the case, Gough said, “are the changing political winds. But we will not rush to judgment.”

The charges against Bryan reflect the stark evolution of the case. Just weeks ago, the prevailing argument by prosecutors was that Arbery’s death was not a criminal offense and that none of the three men should be held criminally responsible.

But the release of the video set off a series of dominoes: the GBI was called in to lead the investigation; Bryan’s neighbors — Gregory McMichael, 64, a retired law enforcement officer, and his son, Travis McMichael, 34 — were charged with murder and aggravated assault; and the case was assigned to a fourth prosecutor, the district attorney in Cobb County, in the metropolitan Atlanta area.

“We are going to make sure we find justice in this case,” Joyette Holmes, the district attorney, said at the news conference on Friday. “We know that we have a broken family and a broken community down in Brunswick.”

After the McMichaels were arrested, Arbery’s family and activists zeroed in on Bryan, urging the authorities to charge him. Lawyers for Arbery’s family have argued that Bryan took part in the chase and “corralled” Arbery.

In a statement after Bryan’s arrest, the lawyers said the family was “relieved,” adding, “His involvement in the murder of Arbery was obvious to us.”

Arbery was killed on a Sunday afternoon near Brunswick as he was running through Satilla Shores, a neighborhood carved from the marshland along the southeast Georgia coast. He was jogging along a tree-lined street when he encountered the McMichaels. “Stop, stop,” they shouted at him, according to the police report, “we want to talk to you.”

In the video, Arbery and Travis McMichael are seen tussling over McMichael’s shotgun as McMichael shoots three times. Arbery then spins around, tries to run and falls to the pavement.

George Barnhill, the prosecutor assigned to the case after the first district attorney recused herself because Gregory McMichael had worked in her office, wrote that he did not believe that Arbery’s killing was a crime.

The McMichaels, he said, had been legally carrying their weapons and believed they were going after a burglary suspect. He also cited the video, which had not yet been shared publicly, and said it showed Travis McMichael acting in self-defense.

In late April, Barnhill stepped away from the case, also citing a conflict. His son works with the Glynn County district attorney who had recused herself and also had worked with Gregory McMichael. The case then moved to another Georgia district attorney, Tom Durden, who said on May 5 that he would take the case to a grand jury. He also summoned the GBI, and about two days later, the McMichaels were arrested.

Lawyers for the McMichaels said their clients maintained their innocence, and said many questions loomed over the fatal confrontation between them and Arbery. “Right now, we are starting at the end,” Jason Sheffield, a lawyer for Travis McMichael, recently told reporters. “We know the ending. What we don’t know is the beginning.”

The arrest of Bryan, who was being held in the Glynn County jail on Friday, came as calls for his prosecution intensified in recent days. Those pushing for his arrest have said Bryan was considered a participant long before the video was shared online. He had been mentioned in the police report of the killing, which was based largely on a Glynn County police officer’s interview with Gregory McMichael, and in a letter Barnhill wrote to the police.

But Bryan, who is known by his nickname Roddie, has contended that he had played an instrumental role in shining a light on Arbery’s death. “If there wasn’t a tape, then we wouldn’t know what happened,” he said in an interview with CNN.

In a statement this week, Bryan’s lawyer said his client’s association to the McMichaels was essentially limited to them being neighbors. He added that Bryan and his fiancée had lost their jobs because of the case and were in hiding after receiving threats.

“There are few things more difficult for a criminal defense lawyer to do” than put “blind faith” in a prosecutor he does not know, Gough said in the statement, which he emailed to reporters late on Monday night.

“But,” he went on, “Roddie and I trust that District Attorney Joyette Holmes and GBI director Vic Reynolds will — in the fullness of time — do the right thing.”

By Wednesday, Holmes and Reynolds decided that investigators had assembled enough evidence to establish probable cause and bring Bryan into custody.

This article originally appeared in The New York Times.