Each week, good news about vaccines or antibody treatments surfaces, offering hope that an end to the pandemic is at hand.

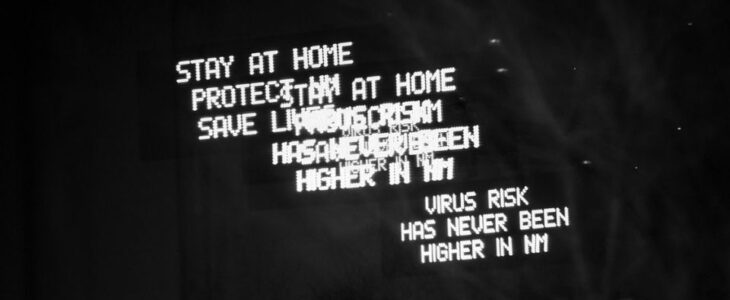

And yet this holiday season presents a grim reckoning. The United States has reached an appalling milestone: more than 1 million new coronavirus cases every week. Hospitals in some states are full to bursting. The number of deaths is rising and seems on track to easily surpass the 2,200-a-day average in the spring, when the pandemic was concentrated in the New York metropolitan area.

Our failure to protect ourselves has caught up to us.

The nation now must endure a critical period of transition, one that threatens to last far too long, as we set aside justifiable optimism about next spring and confront the dark winter ahead. Some public health researchers predict that the death toll by March could be close to twice the 250,000 figure that the nation surpassed only last week.

“The next three months are going to be just horrible,” said Dr. Ashish Jha, dean of Brown University’s School of Public Health and one of two dozen experts interviewed by The New York Times about the near future.

This juncture, perhaps more than any to date, exposes the deep political divisions that have allowed the pandemic to take root and bloom, and that will determine the depth of the winter ahead. Even as the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention urged Americans to avoid holiday travel and many health officials asked families to cancel big gatherings, more than 6 million Americans took flights during Thanksgiving week, which is about 40% of last year’s air traffic. And President Donald Trump, the one person most capable of altering the trajectory between now and spring, seems unwilling to help his successor do what must be done to save the lives of tens of thousands of Americans.

President-elect Joe Biden has assembled excellent advisers and a sensible plan for tackling the pandemic, public health experts said. But Mitchell Warren, the founder of AVAC, an AIDS advocacy group that focuses on several diseases, said Biden’s hands appear tied until Inauguration Day on Jan. 20: “There’s not a ton of power in being president-elect.”

By late December, the first doses of vaccine may be available to Americans, federal officials have said. Priorities are still being set, but vaccinations are expected to go first to health care workers, nursing home residents and others at highest risk. How long it will take to reach younger Americans depends on many factors, including how many vaccines are approved and how fast they can be made.

But even as the medical response to the virus is improving, the politics of public health remain a deeply vexing challenge.

The regions of the country now among those hit hardest by the virus — Midwestern and Mountain States and rural counties, including in the Dakotas, Iowa, Nebraska and Wyoming — are the ones that voted heavily for Trump in the recent election. The president could help save his millions of supporters by urging them to wear masks, avoid crowds and skip holiday gatherings this year. But that seemed unlikely to occur, many health experts said.

“That is outside of his DNA,” said Dr. William Schaffner, a preventive medicine specialist at Vanderbilt University medical school. “It would mean admitting he was wrong and Tony Fauci was right.”

The antidote to hopelessness is agency, and Americans can protect themselves by wearing masks and keeping their distance from others.

“There is pretty broad support for mask mandates even among Republicans,” said Martha Louise Lincoln, a medical historian at San Francisco State University. “But among extreme right-wing voters there’s still a perception that they’re a sign of weakness or a symbol of being duped.”

A study by the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation at the University of Washington estimated that 130,000 lives could be saved by February if mask use became universal in the United States immediately. Masks can also preserve the economy: A study by Goldman Sachs estimated that universal use would save $1 trillion that may be lost to business shutdowns and medical bills.

Biden has said that he intends to tackle the pandemic from his first full day in office, on Jan. 21. But because coronavirus deaths follow new cases by some weeks, any results of his actions may not be apparent before early spring.

The experts generally praised the panel of advisers chosen by Biden, depicting them as reputable scientists who could credibly reach out to many groups hard-hit by the pandemic, including Black and Hispanic Americans.

But several experts, some of whom spoke anonymously to avoid offending friends and colleagues, said the panel needed different skills and a different kind of balance.

Some felt that it should have more scientific expertise, and suggested recruiting more vaccinologists, such as Dr. Paul A. Offit of Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, and more public health researchers, such as Harvard’s Marc Lipsitch and Natalie E. Dean of the University of Florida.

Others said the panel needed more behavioral scientists adept at fighting rumors, which have been a major obstacle.

“We’re facing extremely complex and poorly understood dynamics around disinformation, conspiratorial theories, paranoia and mistrust,” Lincoln noted.

Among the suggested names with those skills were Heidi J. Larson of the Vaccine Confidence Project in London, Carl T. Bergstrom of the University of Washington and Zeynep Tufekci of the University of North Carolina.

Warren suggested consulting marketing experts and recruiting “everyone from Santa Claus to LeBron James” as trusted spokespersons.

Another expert suggested adding Dr. Mehmet Oz, a heart surgeon and television personality who was criticized for promoting hydroxychloroquine on Fox News (he later relented), and possibly even asking Sean Hannity and Tucker Carlson to join, because they are popular with Trump’s base and might be persuaded to accept science that would save the lives of their own viewers.

Biden’s plan for tackling the pandemic is outlined on his website. It calls for far more widespread testing, delivered free; a ban on out-of-pocket costs for medical care for the virus; having the military build temporary hospitals if necessary; cooperation with American businesses to create more personal protective gear and ventilators; more food relief for the poor, and other measures.

All the experts interviewed by the Times praised the plan, but several felt it was not aggressive enough. The pandemic is raging so far beyond control, they argued, that it can be contained only with deeply unpopular but necessary measures, such as rigorously enforced mask laws, closing bars and restaurants, requiring regular testing in schools and workplaces, isolating the infected away from their families, prohibiting travel from high-prevalence areas to low ones, and imposing quarantines that are enforced rather than merely requested.

Many other countries have imposed such measures despite fierce opposition from some citizens, they said, and they have helped.

Biden will inherit the fruits of Operation Warp Speed and oversee their distribution. Members of his transition team, speaking anonymously because they were not authorized to reveal its deliberations, said they were already discussing two sensitive topics: whether to create a secure way for vaccinated individuals to prove they have received both shots, and whether COVID vaccines should ultimately be made mandatory — either by the federal government, or by state governments, employers, school systems or the like.

The next dozen weeks will be long and painful. But spring is likely to bring highly effective vaccines and a renewed commitment to medical leadership, something that has been missing under Trump.

“The CDC will have to be rebuilt, and its guidelines and the FDA’s have to be promptly reevaluated,” said Dr. Robert L. Murphy, director of the Institute for Global Health at Northwestern University’s medical school. “The Biden team will move quickly. It’s not like they don’t know what to do.”

Credit: Yahoo News